After a long time focussing on a new job, a new country, and developing other parts of the website, it is finally time for another blog entry. I do so with the serious but important topic of war. It is difficult to put words on the tragedies of war – the loss of lives, the displacement, the violence and the many years of trauma that follow. With over 10 years of war and unrest in Syria, and now a new war in Ukraine, this seems a good time to pick up on this topic and look at the role of and impact on animals. The devastation to human lives and the countries where war takes place can hardly be overstated. Death, abandonment, injury, displacement, loss of home, family and friends are some of the things faced by victims of war, both human and animal. What follows is a small window into how war affected human as well as nonhuman animals in ancient Mesopotamia.

Animals fighting and dying alongside humans in war

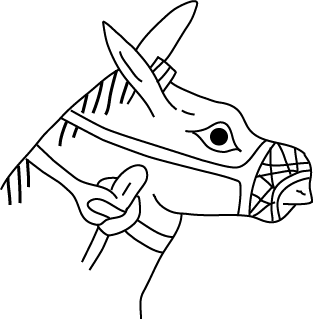

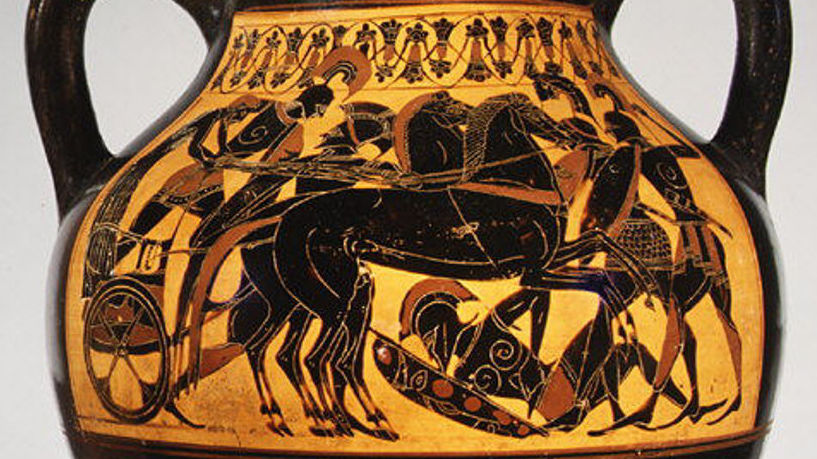

The most striking way that animals occur in war is as part of battle. Some of the earliest evidence of this in Mesopotamia comes from the visual material – plaques, inlays, seals, sealings and the famous Standard of Ur. The Standard of Ur, found in a wealthy tomb in the so-called Royal Cemetery at Ur is dated to the Early Dynastic III period (mid-third millennium BCE). It has two large panels of decoration, the ‘Peace’ side and the ‘War’ side. On the ‘War’ side, we can see wheeled vehicles (sometimes called battle wagons) pulled by a team of four equids – probably either donkeys or the hybrid equids known as kungas. On the lowest register, they are right in the midst of battle, trampling enemies and with soldiers and drivers in the wagon itself.

Another early example of donkeys fighting as part of chariot-teams comes from the so-called ‘Stele of Vultures’. The stele relates to a border dispute between the two city-states of Lagash and Umma in the third millennium BCE, and it records this dispute in both image and inscription. Both sides of the stele are carved, but unfortunately only preserved in fragments. One side shows the god Ningirsu having captured his enemies in a net and, in a register below, probably the same god in his divine vehicle (the part with the animals pulling it has not survived). The other side depicts the king of Lagash, Eannatum, heading a tightly packed infantry unit on foot in the top register; in the second register, he leads another infantry unit from a wheeled vehicle (the part with the animals again not surviving). In a third register, he presides over some of the events of the aftermath of battle, including animal sacrifices, libations and the building of a tumulus for the dead soldiers. The associated inscription mentions how the Lagashite king had burial mounds made for his fallen soldiers and abandoning 60 teams of the enemy’s donkeys and the bones of their personnel. At this point in time, the equids were typically in teams of four, as also on the Standard of Ur. In other words, a total of 240 donkeys of the enemy died in the battle (customarily, the losses of the victor are not recorded).

Equids continue to fight in human wars throughout the second and first millennia. In the second millennium BCE, there are big changes in chariot warfare: the ’true’ chariot appears. This is a much faster and lighter vehicle, with only two wheels that are spoked rather than the earlier disk version. It is usually pulled by a team of two horses instead of the four-team donkey/kunga. In the Late Bronze Age, this combination became widespread and is found not only in Mesopotamia but also Egypt and the entire Eastern Mediterranean. It was an important part of any army, and the Amarna Letters suggest that cities had difficulties defending themselves without a chariotry component.

In the first half of the first millennium, we also see horses and chariots being a part of the Assyrian army – as well as in the armies of their opponents. They are most evocatively depicted on the palace reliefs of Neo-Assyrian kings, but also in earlier Hittite images such as for example the early first millennium orthostats found at Carchemish. Although chariots appear to continue to dominate, the Neo-Assyrian reliefs also increasingly depict horses used as cavalry. Donkeys and other equids were no longer used for direct battle, but were present in other ways, as we will see below, and could be used in emergencies to escape or retreat from the fighting.

However, another animal occurs at this time as ridden and fighting: the camel. The Neo-Assyrians did not themselves have war camels, but some of their enemies did. We thus have heartbreaking images of Arabs and their camels clashing with Assyrians and succumbing to the attack.

The final animal that participated in battle that I would mention here is perhaps more surprising: the dog. Their participation is only known from the second half of the third millennium BCE (read also more here). We do not know their exact role during combat, but they are depicted alongside equids and wheeled vehicles, and recorded in the written records as belonging to army generals. This is just one testament to one of the most enduring close human-nonhuman animal relations. With the dog most likely being the earliest domesticated animal, and the many varieties of the relationship over time – including modern canine units and dogs trained to detect explosives, drugs, money and human diseases, among many others things – this early collaboration is perhaps not as unusual as at first sight.

Animals carrying and providing provisions for the army

A less obvious aspect of animals in war is as carrying provisions for the army on the move. The impact of beasts of burden and traction as facilitators of war would have been immense, and can be illustrated with examples at least as recent as WW I and WW II, where horses, mules and donkeys, along with other animals such as dogs and messenger pigeons participated in large numbers. Many died: almost half a million horses are recorded as lost during WW I. Although other animals could be used to carry provisions (for example, cattle and human porters), donkeys were most commonly used for this purpose in ancient Mesopotamia. It is of significance mostly for an army on the offensive – that is, an army moving in order to attack, and therefore needing to bring provisions with it. Especially the large contingents of the Neo-Assyrians moved over very long distances, and sometimes besieged far away cities for months or even years on end. These would have required substantial amounts of food and water, along with other goods – for both humans and other animals.

This much less dramatic aspect is not usually the subject of the visual evidence. It can occasionally be found indirectly in the written sources, although even then usually only when there are problems, as a letter found in the city of Mari shows:

When we departed (to get) here, Ishme-Dagan, together with his troops, started out in the middle of the night for Ekallatum. And the grain that Ishme-Dagan transported on his donkeys from the namashshum fo Ashkur-Addu did not arrive in Razama. And his donkeys returned without their load to Ekallatum. They (say), ‘Ishme-Dagan is hungry. There is no grain whatsoever in the land.’

Hempel 2003, 402-403

Animals as mediators

Beside carrying the provisions, the animals themselves also were provisions. While the diet of the soldiers on the move almost certainly consisted primarily of grain-based food, it may occasionally have included meat. Certainly, significant amounts of sheep were also part of the army, as they were crucial for divination. Divination of sheep livers and entrails (extispicy/hepatoscopy) was an integral part of the army practices from at least the Old Babylonian period onwards. It involves the sacrifice of a sheep and subsequent inspection of its liver. This procedure was used to make enquiries about the next strategic step, and diviners were part of the army personnel. Surviving records explain how to interpret specific features found on the liver – for example a discolouration, lump or unusual shape:

If an enemy plans an attack against a city and its plan is revealed, it will look like this.

If the enemy musters which hostile intent but the prince’s [army(?)], however considerable it may be, is not powerful enough, (it will look like this).

Ulanowski 2020, 45

The practice is depicted in palace reliefs and other art. The exact number of sheep killed in this manner is impossible to establish, but given the prevalence of the practice, it must have been quite substantial and added up to many animals in total. To see that animal sacrifices occurred as part of the rituals of war at least as early as the third millennium BCE, we can return to the Stele of the Vultures. In the register where the Lagashian king presides over post-battle rituals, a priest making a libation stands on a pile of headless animals, presumably sacrificed for the occasion.

The aftermath of war

In the aftermath of war, beyond those fallen on the battlefield, animals were present in two ways: as scavengers and as part of the loot. Starting with the former, the Stele of the Vultures again provides a good early example. In the top register with the king on foot in front of an infantry contingent, another fragment of the stele shows vultures carrying human heads and other body parts, picked up from the battlefield (hence also the name of the stele). Similar images occur in other depictions; on a stele of Sargon found in Susa, dogs also participate in this scavenging activity. Such motifs are part of the ideology or we might even say propaganda of victorious rulers, and we can also here detect a repetition of this theme in the Neo-Assyrian repertoire.

Many animals, especially medium to large-sized mammals, were also important resources. The breeding, rearing, herding and training of various animals would have been an enormous and very expensive affair. For example, the horses used in war would require years of breeding, rearing and training by specialists, which would have required extensive management and administration. Wars were fought for a variety of reasons, but access to resources would have been one of the key ones, even if official narratives offer a different version. Even the Standard of Ur, with its lines of sheep, goats and equids (and some fish!), indicates the significance of (animal) resources. Animal loot was carefully recorded by the Neo-Assyrians along with people and goods. Just as mass deportations of humans was a common practice, so was that of the captured animals – they were displaced and moved long distances, often to the Assyrian heartland and capital.

These are just some of the ways that animals were part of and caught up in human conflict in ancient Mesopotamia. It is far from an exhaustive account. For example, it is harder to reconstruct the impact on smaller and wild animals. One might here consider the heartbreaking devastation to animals caused recently by the wildfires in Australia – not a case of a human war, but a possible indication of the more ‘invisible’ damage of laying waste and setting fire to cities and animals such as dogs, foxes, rodents getting caught in it. Companion animals may equally lose their home, source of food and co-habitants. Stories of modern war naturally focus on the devastation to humans, but in recent reports on Ukranians forced to leave behind their animal companions, we get a glimpse of yet another aspect of the cruelty of human wars.

References and further reading:

Bahrani, Z. Rituals of War: The Body and Violence in Mesopotamia. (Zone Books, 2008).

Heimpel, W. Letters to the King of Mari: A New Translation, with Historical Introduction, Notes, and Commentary. (Eisenbrauns, 2003).

Lau, D. Tiere im Krieg: Der mesopotamische Raum. Tiere und Krieg, 21–33 (Neofelis, 2017).

Tsouparopoulou, C. The “K-9 Corps” of the Third Dynasty of Ur: The dog handlers at Drehem and the army. Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie 102, 1–16 (2012).

Ulanowski, K. Neo-Assyrian and Greek Divination in War: Ancient Warfare Series Volume 3. (Brill, 2020).