I have been looking forward to this post for some time now. Akshyeta Suryanarayan works on organic residue analysis, which is a technique that can help us understand how pottery was used in the past – including tracing animal products such as meats, dairy and beeswax. So it combines two of my favourite interests: ceramics (yes, I’m one of those archaeologists) and human-animal relations. Then there’s the added bonus of it all being discussed in the frame of the archaeology of the fascinating Indus Valley.

Hi, I’m Akshyeta Suryanarayan, a PhD candidate in archaeology at University of Cambridge. This blogpost discusses my PhD research which is focused on investigating food in the Indus Civilisation through ceramic residue analysis.

My research is focused on the urban phase of the Indus Civilisation (c. 2600-1900 B.C.), known as South Asia’s first urban civilisation, with sites located across present-day Pakistan, India, even Afghanistan. This civilisation is enigmatic to archaeologists because unlike its contemporaries in Egypt and Mesopotamia, its script is undeciphered and there is not much obvious evidence of social or political hierarchies, either in the presence of monumental architectural structures like palaces or temples, or obvious power symbols, like big statuary or stelae.

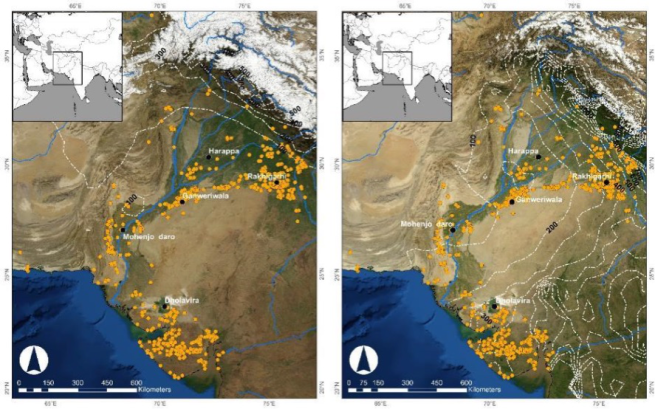

The one thing that the Indus Civilisation is known for is its cities: cities like Mohenjo-daro, Harappa and Ganweriwala (unexcavated) in Pakistan, and Dholavira and Rakhigarhi in India with fired mud-brick architecture, walled enclosures, streets, drains, wells and platforms.

Although some of these cities have large buildings and residential blocks that likely served some public and/or specialised social/political function, for example, the Great Bath, ‘Pillared Hall’ and the ‘stupa’ at Mohenjo-daro,[1] we are not sure about how society was structured or who was in control within a single city or across cities.

Most Indus scholars today believe that power within cities was likely shared across groups in a heterarchical system. This unique aspect of the Indus Civilisation often means that it is not included in discussions about early states. And yet, it is hugely important to our understanding of the many iterations of complex societies. Additionally, the Indus ‘city’ has had so much focus in scholarship that not much is known about rural settlements, which greatly outnumber the cities. The relationship between rural and urban settlements is also not well-understood (a new paper by Danika Parikh and Cameron Petrie expands upon rural-urban dynamics in the Indus Civilisation further). My PhD attempts to understand the relationship between urban and rural populations in terms of their food economy.

Indus pottery and food

Although striking, buildings and beads are not the most common remnant of the Indus civilisations. That honour goes to another type of object that most archaeologists either love or hate, and that others most commonly make fun of archaeologists about: pottery, or rather, broken bits of it. Fired clay is a wonderous material: it is fragile at the same time as it is virtually indestructible, and it can be used to investigate a range of aspects of social life in the past. Copious amounts of broken potsherds are found at Indus sites and have been used as a proxy to characterise Indus chronology, craft production and organisation, and social identity. While investigating how pottery was made at different sites can tell us a lot about organisational networks, ultimately, pots, jars, bowls and plates were containers for organic products and foodstuff, used for boiling, stewing, brewing, mixing, serving, and storing. The use of different types of Indus pottery has not been investigated in a systematic fashion, which is an aspect my PhD addresses.

The porous nature of ceramic makes it ideal for absorbing fats and oils from foodstuff that are released or used as part of the cooking process. These fats and oils (or lipids) bind with the ceramic and are relatively well-protected from degradation and leaching by water due to their hydrophobic nature. Thanks to different chemical techniques, it is possible to use extraction methods involving solvents to remove lipids from within the ceramic fabric, separate the complex mixtures of compounds that make up the lipid extracts, and identify unique components within extracts. Some of these compounds can be matched with existing reference materials (taking into account degradation processes), making it possible to identify products like beeswax, plant waxes, fish, heated products, or even bitumen and resinous materials. Additionally, the stable carbon isotope values of specific lipids are determined and compared to various modern animal fats like the adipose fats (meat) of ruminants like sheep/goat, cattle, and deer, non-ruminant animals like pigs or fowl, equines like horses, and dairy fats. This means that we can identify whether vessels were used for processing dairy products like milk, cheese, or yoghurt, or for the meat of different animals. The use of ceramic lipid analysis thus enables an investigation into the cultural use of vessels, as well a new means to understand how food was meaningfully processed and created in vessels.

Why food?

I am particularly fascinated by food in archaeology and lipids in ceramic vessels as I think they provide a unique lens by which to investigate the blending of the natural environment with human material culture and the ontological/social/political; if one could ever set up neat categories of human experience that way. Each step involved in the production and processing of food is influenced by complex decisions. The selection of ingredients into a vessel involves knowledge of the environment: from the managing and processing of crops; raising, managing, and butchering of animals; or gathering of plants and forest products; with choices of ingredients based on factors like seasonality, cultural ideas about ‘what is good to eat’, memory (“my grandmother made it this way”), and taste preferences. Certain types of foodstuff encode all kinds of social, ontological, and/or cosmological meanings. Cooking or processing of food involves skill, specialised technique and is a sensorial practice. It is here where special tools (knives, grinding stones) or vessels are used for the desired end-product. As a time-consuming, laborious process, it is usually relegated to specific people (this is often gendered – ask yourself who cooks your meals at your home today?), forming a ‘community of practice.’ Finally, in the serving and sharing (or avoidance) of food in everyday or ‘special’ occasions, a variety of ‘commensal politics’ are played out, which can “signal rank or rivalry, solidarity and community, identity and exclusion, and intimacy or distance”[2].

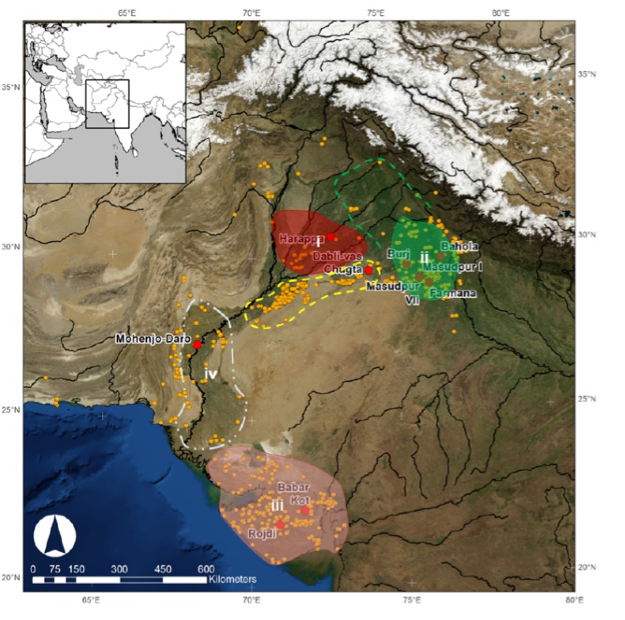

While all these aspects of food are fascinating, it can be challenging to access them in archaeology, especially when one has little access to textual records or imagery concerning everyday habits. Additionally, early excavations were notoriously poor at collecting and recording artefacts like charred seeds and animal bones, which form the basis of our reconstruction of subsistence practices in the past. In the context of the Indus Civilisation, although excavation methods have much improved, there are a variety of issues that affect interpretation, including the poor preservation of remains, and patchy collection of detailed spatial and chronological information. Despite the somewhat fragmentary evidence, debates about food production are interwoven with concepts of urbanism, environment, and ideas about the uniformity or diversity of practices across Indus settlements. In my thesis I have put together available evidence for agricultural and pastoral practices across the Indus Civilisation, but focus specifically on northwestern India, which is from where I have accessed pottery samples for lipid analysis from a range of rural and urban settlements, thanks to the Land, Water and Settlement and TwoRains project, and Deccan College, Post Graduate and Research Institute, Pune.

Ancient Indus food

There is a huge range of scholarship about plants and animals in the Indus Civilisation, which already tells us a lot about Indus food. Very briefly, a range of winter and summer crops (wheat, barley, winter and summer pulses, millets and rice) were grown in the Indus Civilisation. A recent paper by Cameron Petrie and Jennifer Bates hypothesises that the entire region can be broadly divided into four geographical zones where, 1) primarily winter crops were grown with some summer crops; 2) primarily summer crops were grown with some winter crops; 3) primarily summer crops were grown, and 4) primarily winter crops were grown. These zones coincide with the availability of summer and winter rainfall across the region and match available archaeobotanical evidence.

As far as animals are concerned, Indus populations seem to have preferred cattle/buffalo, with between 70-80% of faunal assemblages at sites made up of the remains of these large ruminants. Sheep/goat make up between 10-20% of faunal assemblages, while non-ruminants such as pigs and birds and freshwater fish contribute to a small percent of the animal bone remains at sites (with exceptions at coastal sites). Wild animals such as deer and rabbit are also found (no horses or equids are found at Indus sites, sorry Laerke!). No clear regional differences have been observed with respect to animal remains; except for occasional site-specific variations. On the basis of this, Indus scholars have given primacy to cattle at Indus sites: it is assumed (and occasionally demonstrated), that cattle were used for traction at agricultural sites, sustained a thriving dairy economy, and eventually consumed.

It appears that although Indus populations grew a variety of crops with clear regional variation across the Greater Indus region, there are no clearly identifiable regional differences (yet) between the types of animals they chose to consume. Studies of starch grains recovered from the surfaces of stone tools have revealed tantalising evidence of the processing of ginger, aubergine and mango, giving us a glimpse of vegetables, fruits and condiments that are generally missing in the archaeobotanical record, although detailed evidence is not yet available. My thesis is adding to our knowledge about Indus food by detecting what kinds of organic products can be identified in different ceramic vessels, especially dairy products, and whether there were differences between foodstuff processed in urban and rural Indus sites in northwest India and over time, from the urban to the post-urban period.

The results from my analyses will soon be published. They open up a variety of questions about how Indus lifeways were materialised through everyday acts of cooking and eating. These include how food practices defined the relationship between people, plants and animals. Did urban and rural residents process similar types of food, or were food practices shared regionally? What could this mean about rural and/or urban identity and commensality?

However, it is important to remember that there are methodological limitations and interpretational challenges associated with studying highly degraded organic remains. For example, it is not possible to reconstruct ‘recipes’, or detect very specific ingredients processed in the vessels. There are also issues related to the untangling of mixtures of products processed in vessels. Despite this, a focus on ancient food helps us look beyond just ‘subsistence’ or animals and plants alone and adds a social dimension to everyday acts of sustenance. Studying culinary practices within the Indus Civilisation helps us appreciate how both rural and urban populations were active agents in maintaining a food economy.

Understanding ancient food in this region is particularly important when we consider the incredible diversity of food in South Asia today. Food has complex ontological, ritual, social and political meanings in different South Asian communities, where it is deeply intertwined with caste, ‘tribe’ and religious identity. Food is also tied into colonial, neo-colonial and nationalist ideologies and agendas, and recently, in India, meat-eating has become a virtual battleground where debates about morality, nationality and religiosity are waged. In this context, studying ancient food practices and questioning the foundations of what constitutes our idea of ‘South Asian’ or ‘Indian’ cuisine is vital.

Thanks for reading!

All www.harappa.com images are copyright of J.M. Kenoyer/Harappa.com, Courtesy Dept. of Archaeology and Museums, Govt. of Pakistan.

Notes

[1] That was possibly not a Buddhist stupa but an Indus-period building contemporaneous to other structures in its vicinity (see Verardi, G. & F. Barba. 2010. ‘The So-Called Stupa at Mohenjo-Daro and Its Relationship with the Ancient Citadel’. Pragdhara 19: 147-170).

[2] Appadurai, A. 1981. ‘Gastro-Politics in Hindu South Asia’. American Ethnologist 8 (3): 494-511.