For you, your household, your wives, and for your sons, your country, your chariots, your horses, your magnates may all go very well. [1]

This is a greeting so standardised in the Amarna Letters that sounds almost formulaic. It reveals the important role that horses and chariots had achieved in the affairs of the rulers of the Eastern Mediterranean by the 14th century BCE. They were essentially part of the extended royal household.

The Amarna Letters is a collection of tablets found at the site of el-Amarna, the ancient city established by Akhenaten in the Egyptian 18th Dynasty. They are mostly letters written to the Egyptian pharaoh from various local rulers and vassals in the Near East and Cyprus. They were written in cuneiform, mainly Akkadian, but there are also a few in other languages.

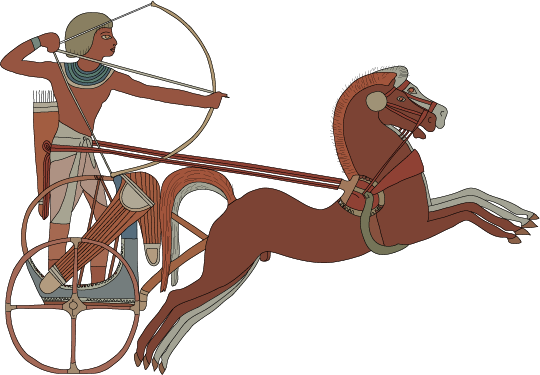

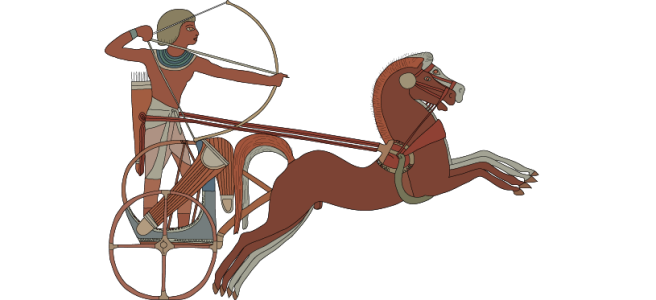

By the 14th century BCE, the fast, light, two-wheeled chariot had become common and armies were considered significantly handicapped without it. Chariots now had spoked wheels, were pulled by two horses (as opposed to donkeys), and were accompanied by the use of bits with two reins. This was a great improvement to the earlier heavy vehicles and unwieldy communication system of the third millennium and beginning of second millennium BCE. Armies without a chariot division were seriously disadvantaged, although exactly how they were used during battle is still uncertain.

The letters contain many references to the use of horse-drawn chariots for military purposes. For example:

Letter from Rib-Hadda, ruler of Ṣumur (a town in the Levant), asking the pharaoh for help (EA 103):

As the entire garrison has fled from Ṣumur, may it seem right in the sight of the lord, the sun of all countries, and give me 20 pairs of horses, and send an auxiliary force with all speed to Ṣumur in order to guard it.

Or this letter from Artamanya of Siribashani (EA 201):

I am herewith, along with my troops and my chariots, at the disposition of the archers wherever the king, my lord, orders me to go.

Chariots were not just used for battle, though. The period witnessed an excessive amount of ‘gift-exchange’ between rulers. Horses and chariot were part of the luxury goods that were exchanged. As in a letter from the Mitanni king Tushratta writes to the pharaoh (EA 19),

I herewith send as my brother’s greeting-gift: 1 gold goblet, with inlays of genuine lapis lazuli in its handle; 1 maninnu necklace, with a counterweight, 20 pieces of genuine lapis lazuli, and 19 pieces of hold, its centerpiece being of genuine lapis lazuli set in gold; 1 maninnu-necklace, with a counterweight, 42 genuine ḫulalu-stones, and 40 pieces of gold shaped like arzallu-stones, its centerpiece being of genuine ḫulalu-stone set in gold; 10 teams of horses; 10 wooden-chariots along with everything belonging to them; and 30 women and men. [2]

The rulers ostensibly send each other these fancy and expensive items as ‘gifts’, but in true social-contract fashion, the expectation is to receive even fancier ‘gifts’ in return. It is basically elite trade shrouded in diplomatic language. Despite this diplomatic framework, the language is sometimes less than subtle. In the same letter, Tushratta asks that in return,

May my brother send me in very great quantities gold that has not been worked, and may my brother send me much more gold than he did to my father. In my brother’s country, gold is as plentiful as dirt.

We also hear of horse-drawn chariots used as appropriate escorts for royalty, and horses are used by messengers (probably ridden rather than pulling a chariot). Swift and white horses were particularly desirable; other sources suggest that white horses were preferred, and as a result, were more expensive.

Zimri-Lim, the king of Mari writes (ARM X 147),

About the white horses that are from Qatna, of which you are always hearing: those horses are really fine!

Unfortunately, the material of the Near East at this period does not include images that distinguish colour, but Egyptian wall paintings sometimes provide a hint. They show both white and chestnut horses, often together as a single team, and even dappled horses.

The Amarna Letters are invaluable as a source for the Late Bronze Age, and especially for the ‘international spirit’ of connections and trade between the regions of the Eastern Mediterranean that characterises this period in history. They also give us a wonderful insight into the way horses and chariots were seen and exchanged as highly valued prestige goods.

Notes

- The translations given here are adapted from William Moran’s The Amarna Letters (1992).

- The word ‘brother’ is not a biological marker here; it is used between rulers who consider each other equal.

One thought on “The Amarna Letters”